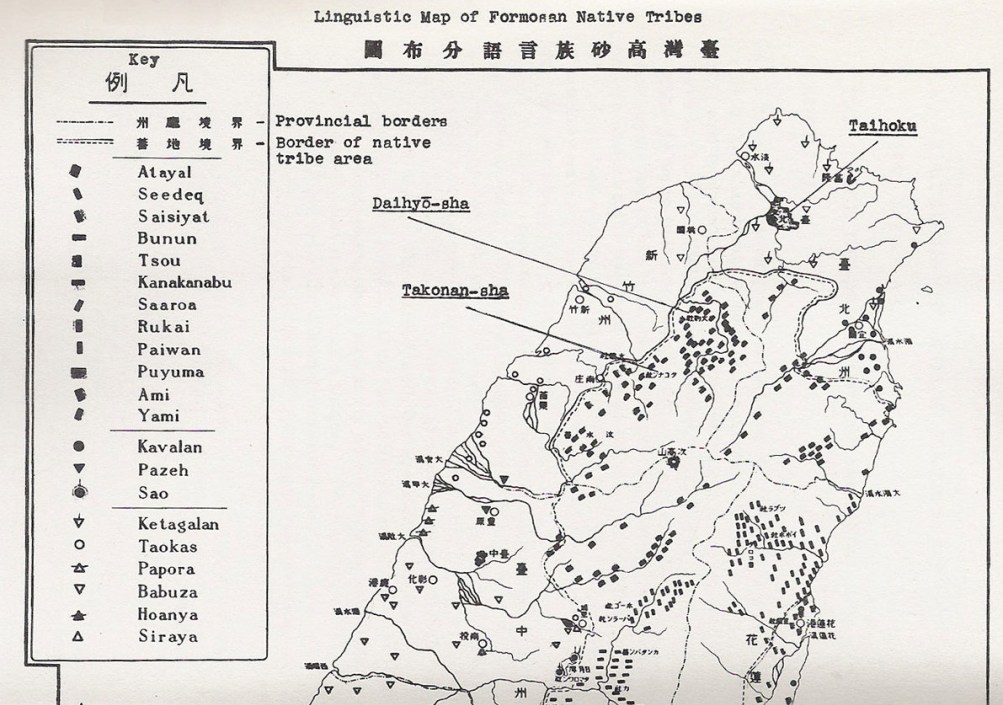

Yet the inclusion of the Pingpuzu was a radical act—arguably the boldest aspect of the whole event. Every preceding government of Taiwan had refused to acknowledge Pingpuzuactivists’ claims to indigeneity. By explicitly mentioning them in her apology, President Tsai gave legitimacy to the idea that Taiwan’s “true” indigenous population — officially only about 530,000, or 2.3% of the total — is significantly larger than recognized."

|

My piece at Ketagalan Media is on the Pingpuzu Aborigines included in Tsai Ing-wen's apology ceremony on August 1: "When President Tsai Ing-wen made a historic apology to indigenous peoples on August 1, she addressed her remarks not only to the country’s 16 officially recognized aborigine (yuanzhumin 原住民) tribes but also to the “Pingpu ethnic group,” or Pingpuzu (平埔族) — descendants of Taiwan’s culturally assimilated indigenous peoples who are not officially recognized by the government as aborigines. In the flood of commentary that has followed Tsai’s apology, the presence of Pingpuzu representatives in the ceremony has attracted little attention. Yet the inclusion of the Pingpuzu was a radical act—arguably the boldest aspect of the whole event. Every preceding government of Taiwan had refused to acknowledge Pingpuzuactivists’ claims to indigeneity. By explicitly mentioning them in her apology, President Tsai gave legitimacy to the idea that Taiwan’s “true” indigenous population — officially only about 530,000, or 2.3% of the total — is significantly larger than recognized." Read the whole thing here.

0 Comments

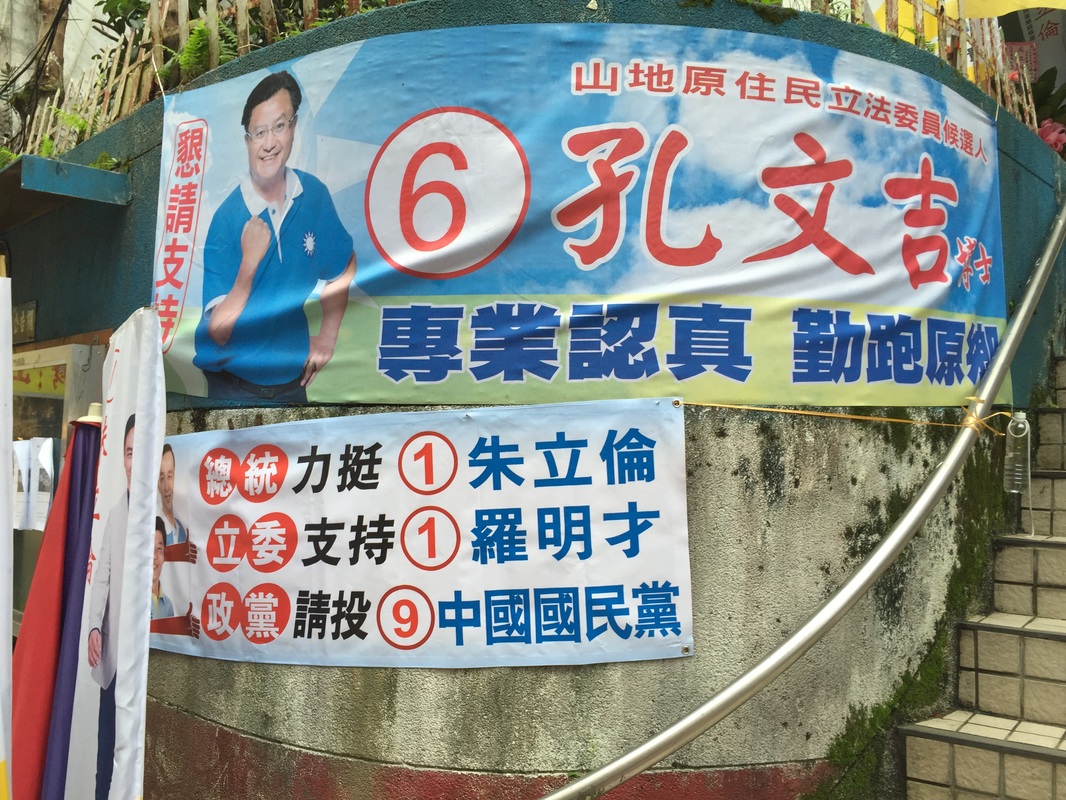

August 1 is Indigenous Peoples' Day in Taiwan--a day that usually passes without much media attention. This year is different: President Tsai Ing-wen is planning to issue a formal apology on behalf of the Republic of China government to Taiwan's indigenous peoples and to outline her government's indigenous policies. That has now become a partisan issue. Five of the six aborigine (原住民 yuanzhumin) district representatives in the current Legislative Yuan are going to skip the event; the only one to attend is the only district DPP member, Chen Ying (陳瑩). The other two legislators, Kolas Yotaka (谷辣斯·尤達卡) of the DPP and Kawlo Iyun Pacidal (高潞·以用·巴魕剌) of the NPP, are both party list legislators, and so have to take their own party line into greater account. Although they're often overlooked in writing about Taiwan's electoral politics, Taiwan has reserved seats in the Legislative Yuan for aborigine representatives since 1972. Today, representatives from these districts hold more than 5% of the total seats in the legislature (6/113)--if they were all part of the same party, they would be the third largest in the LY, ahead of both the NPP and PFP. For anyone interested in learning more, I have a CDDRL working paper on the history of these seats and the evolution of aborigine representation in the Legislative Yuan. The abstract is below. The Aborigine Constituencies in the Taiwanese Legislature

The Republic of China on Taiwan has long reserved legislative seats for its indigenous minority, the yuanzhumin. While most of Taiwan’s political institutions were transformed as the island democratized, the dual aborigine constituencies continue to be based on an archaic, Japanese-era distinction between “mountain” and “plains” aborigines that corresponds poorly to current conditions. The aborigine quota system has also served to buttress Kuomintang (KMT) control of the legislature: the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and “pan-indigenous” parties have been almost entirely shut out of these seats. Nevertheless, aborigine legislators have made a modest but meaningful difference for indigenous communities. The reserved seats were initially established during the martial law era as a purely symbolic form of representation, but during the democratic era they have acquired substantive force as well. Taiwan’s indigenous peoples have not always been well-served by their elected legislators, but they would be worse off without them.  Doing some catching up here...on April 19th we hosted Julia Huang for a talk on the Buddhist charity organization Tzu-chi (慈濟). Dr. Huang is currently a visiting scholar at the Ho Center for Buddhist Studies at Stanford University, and a Professor of Anthropology at National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan. She has published articles in the Journal of Asian Studies, Ethnology, Positions, Nova Religio, the Eastern Buddhist, and the European Journal for East Asian Studies. Her book, Charisma and Compassion: Cheng Yen and the Buddhist Tzu Chi Movement (Harvard University Press, 2009) is an ethnography of a lay Buddhist movement that began as a tiny group in Taiwan and grew into an organization with ten million members worldwide. Huang has recently completed a book manuscript, The Social Life of Goodness: Religious Philanthropy in Chinese Societies (with Robert P. Weller and Keping Wu). She is currently working on a project on the Buddhist influences on cadaver donations for medical education in Taiwan. The End(s) of Compassion?: Buddhist Charity and the State in Taiwan

The Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi (Ciji) Foundation from Taiwan is perhaps one of the largest Buddhist charities in the Chinese world today. This talk traces how Tzu Chi developed under the “regime of civility” in Taiwan. The same regime also contributed to the recent controversies between Tzu Chi and the Aborigines. I argue that the tension between the Buddhist non-governmental organization and the Christian Aborigines has to do with the inequality under the regime of civility: on the one hand, the Aborigines have been marginalized as the “subject” of the civility campaign by the state; and, on the other hand, the same regime of civility is what allows the Buddhist charity to thrive in civil society. This talk raises the question whether civility could turn against civil society.  On December 2, the Taiwan Democracy Project will hold a special roundtable session to discuss the results of Taiwan's local elections on November 29. The event is free and open to the public, and lunch will be provided. You are encouraged to RSVP at the official event page. Panel speakers will include Dennis Weng, visiting assistant professor of political science at Wesleyan University; Thomas Fingar, a Distinguished Fellow at the Asia-Pacific Research Center in the Freeman Spogli Institute at Stanford University; Winnie Lin, a Stanford undergraduate; and me. Some context on the elections follows. On November 29, Taiwan will hold comprehensive local elections which will decide a huge number of offices, from the Taipei mayor all the way down to village and ward chiefs. These elections are also being called the "9-in-1" (九合一) elections, because they combine elections to nine separate offices. By the time Taiwan's transition to democracy finished in 1996, elections to directly administered municipalities, counties and cities, townships, village chiefs, and ward chiefs were all held at separate times. Along with separate national elections for the National Assembly (beginning in 1991), the Legislative Yuan (1992), and the presidency (1996), that meant Taiwanese voters were going to the polls about once a year. That's a lot.

In recent years, on the other hand, the trend has been toward consolidation. A set of amendments in 2005 changed the legislative term length from three to four years to coincide with the presidential term, and starting in 2012 both elections were held on the same day, creating a single national election every four years. The National Assembly was abolished in the same reform. Then county and county-level city terms were temporarily extended to align with the election cycle of the special municipalities of Taipei and Kaohsiung, for the first time creating a single local election day: The races to be decided in the 2014 election:

In addition, about 25 township-level jurisdictions with significant "mountain aborigine" populations hold special status as "self-governing" areas (自治區). In a nod to the special status of aborigines in Taiwan, local government laws require that the township heads in these areas be aborigine. This became a point of some contestation after several counties (Taipei County, Taichung City and County, and Kaohsiung City and County) were merged and raised to centrally-administered municipality status in 2009. As part of this reform, townships and towns in these areas became districts (區), which have appointed, not elected, leaders. As a consequence, several self-governing townships lost the right to elect their leaders--Wulai Township, a popular tourist destination a short trip south of Taipei, was one. In December 2013 the Legislative Yuan passed an amendment to restore the right to elect the leaders and councilors of these former townships. As a consequence, two more elections were added:

So that's how they got to "9-in-1".  On October 3, 2014, the Taiwan Democracy Project will kick off our yearly speaker series with a seminar by Scott Simon on the politics of indigenous rights in Taiwan. Prof. Simon is an anthropologist in the School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies at the University of Ottawa, where he holds the Research Chair in Taiwan Studies. His talk is entitled, "All Our Relations: Indigenous Rights Movements and the Bureaucratization of Indigeneity in Taiwan." The abstract is below. The talk is free and open to the public; you are encouraged to RSVP at the official event page here. Prof. Simon holds a Ph.D. in anthropology from McGill University, and began his career working in the anthropology of development. His previous publications include Tanners of Taiwan: Life Strategies and National Cultures (2005) and Sweet and Sour: Life-Worlds of Taipei Women Entrepreneurs (2003). Since 2004, he has worked extensively on ethnographic research with Truku and Sediq groups in both Hualien and Nantou counties, which formed the basis for his most recent book, published in French: Sadyaq Balae!: L'Autochtonie Formosane dans Tout Ses États (2012). Today, he is one of the most prominent scholars writing on the Taiwanese state's relations with indigenous "aborigines" (原住民), who by official counts make up about two percent of the island's population. All Our Relations: Indigenous Rights Movements and the Bureaucratization of Indigeneity in Taiwan

Taiwan’s indigenous social movement, active since the 1980s, has successfully lobbied to get indigenous rights included in the Republic of China Constitution, to create a cabinet level Council of Indigenous Peoples, and to pass the 2005 Basic Law on Indigenous Peoples. Taiwan’s indigenous social activists have also become regular participants in United Nations indigenous events. Especially during the Chen Shui-bian presidency, foreign observers often suspected that the state instrumentalized “indigeneity” to claim a distinct identity from China. Events since 2008, however, demonstrate that the indigenous rights movement has maintained its own momentum and that the indigenous peoples have interests that cannot be reduced to issues of national identity or party politics. In fact, the indigenous people overwhelmingly support the KMT, and indigenous movements are involved in both “pro-unification” and “pro-independence” political networks. Most indigenous social movement leaders, as well as ordinary indigenous people, hope that their movement can make progress in indigenous rights in ways that transcend the “blue” and “green” division between Han Taiwanese. This talk will explore the diversity of the indigenous movements, their mobilization strategies, and values since Ma Ying-jeou was elected President of the ROC in 2008. |

About MeI am a political scientist with research interests in democratization, elections and election management, parties and party system development, one-party dominance, and the links between domestic politics and external security issues. My regional expertise is in East Asia, with special focus on Taiwan. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed