Equally striking was the swing away from the KMT at lower levels, where the party’s candidates have traditionally been more insulated from national trends: the number of KMT councilors dropped from 419 to 386 (out of 907), and KMT township heads fell from 121 to 80 (out of 204). The KMT now holds a majority on only 6 of 23 city and county councils—remarkable for a party that could once count on control of the vast majority of local offices to help it mobilize votes for national elections. The consistent swing away from the KMT across every jurisdiction in Taiwan suggests that this was a “wave” election—unhappiness with the ruling party and its chairman, President Ma Ying-jeou, drove a national slump in KMT support that showed up in vote totals nearly everywhere. Indeed, this was arguably the KMT’s worst-ever performance in a local election: only 1997 comes close, and the fact that all local offices were on the ballot this year, including the special municipalities, makes this a more consequential defeat than that election. (These figures are drawn from a presentation I gave at a Stanford roundtable on December 2; the slides from that talk are available here.)

It’s a little late for me to weigh in on the debate over why the KMT fared so badly—plenty of other people have done that already, and the impact is rapidly fading into the past as Taiwanese politics churns along. Instead, in this post I want to look forward and ask: what does the 2014 election tell us about future election outcomes in Taiwan, especially the 2016 presidential race?

The unquestioned assumption in most commentary in Taiwan is that the KMT’s recent electoral rout bodes poorly for its chances in the coming presidential and legislative elections, now tentatively set for January 2016. Some commentators have argued that the 2014 result indicates a fundamental electoral “breakthrough” for the DPP, rather than a temporary shift away from the KMT due to recent scandals and the unpopularity of President Ma, and that the DPP should be the favorite going into 2016.

This is not self-evident. To see why, we need only look at the last time around. In the last local elections in 2009-10, the DPP’s candidates for county and city executives actually won more total votes than did the KMT: 5,755,287 to 5,463,570. That turned out not to presage a DPP victory in the presidential race in 2012: Tsai Ying-wen lost to Ma Ying-jeou 51.6% to 45.6%.

Why the big difference? One reason is simply that they were held at different times: Taiwan was in a major recession (as was much of the world) in 2009-10, whereas by 2012 economic growth had bounced back. Another is that the relative importance of factors affecting mass voting behavior in local elections is different from national ones: ideological positioning and the state of the national economy, among other things, are likely to play a stronger role in vote choice in 2016 than they did in the local elections. The personal qualities of the candidates matter, too, and there’s always the possibility of a third candidate emerging as a serious contender, as happened in the 2000 presidential election.

So, until we know who the candidates are, what platforms they'll run on, and how the economy is likely to be doing, we should be cautious about forecasting a win for either major party. Nevertheless, might the 2014 elections at least tell us something meaningful about the relative appeal of the DPP and KMT right now? If we assume all the other factors will cancel each other out, doesn't the last election tell us the DPP will enjoy a generic partisan advantage going into 2016?

Not necessarily, and the reason is turnout. In general, it's 10-15 percent higher in presidential elections than local ones. If these extra voters who show up at the polls in presidential elections disproportionately support the KMT, then the local results are going to give an underestimate of the KMT’s expected vote share in 2016. So it would be nice to know how much of the DPP's success is due to KMT-leaning voters staying home, versus the DPP winning more votes. To figure that out, we need to dig into the raw vote totals a little more.

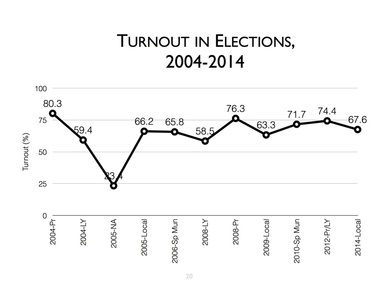

Let’s start with the basic numbers. Here are the turnout figures for 2012 and 2014:

- 2012: 13,452,016 votes cast, or 74.4 percent of all eligible voters;

- 2014: 12,512,135, or 67.6 percent.

Now, how about the partisan breakdown? Here's the vote totals for each party in 2012 (presidential election) and 2014 (county/city executives):

- 2012: Tsai Ying-wen (DPP): 6,093,578

- 2012: Ma Ying-jeou (KMT): 6,891,139

- 2014: DPP candidates: 6,684,089*

- 2014: KMT candidates: 4,990,667

Notably, the DPP candidates (including Ko Wen-je) together polled almost 600,000 votes more than Tsai did in the 2012 presidential race, even as turnout declined! So while the KMT had a disastrous drop from 2012 to 2014, there was also a significant increase in support for the DPP in 2014 above and beyond its support in the presidential election. Clearly, this is not just a story about asymmetric turnout of each party's base supporters, with pan-Blue voters sitting this one out. Instead, the DPP appears to have made big absolute gains as well: the party's vote total in 2014 was only about 200,000 short of what Ma Ying-jeou won in 2012, in a higher-turnout election.

(For those interested in digging further into the numbers, I've put all these data in an Excel file, which can be accessed below):

| 2012-2014_elections_comparison.xlsx |

There's one caveat to this conclusion, and it's a big one: the result in Taipei was quite anomalous. Ko Wen-je in Taipei ran as an independent and deliberately avoided associating too closely with the DPP during the campaign, and the KMT's candidate Sean Lien (連勝文) was a particularly poor nominee. In 2016, the DPP is not going to be able to replicate what Ko did and carry Taipei by over 200,000 votes. Given Taipei's size, we're clearly overestimating the DPP's probable support if we count all the votes for Ko in 2014 as likely votes for the DPP in 2016. On the other hand, there were several other counties where the DPP didn't run a candidate; the party will undoubtedly add some votes in these places in 2016. Any inference about 2016 depends among other things on the net effect among these jurisdictions.

To get a better sense of the size of this effect, I took out the votes from the five "oddball" jurisdictions where the DPP did not run a candidate: Taipei, Hsinchu County, Hualien, Lienchiang, and Kinmen. The comparison of vote totals in the other, "normal" jurisdictions is below:

- Tsai 2012 (minus oddballs): 5,321,816

- DPP 2014 (minus oddballs): 5,830,106

So in the places where it ran a candidate, the DPP bested its 2012 vote total by over 500,000. That's especially impressive because there were double-digit declines in turnout from 2012 in New Taipei, Taoyuan, Tainan, and Kaohsiung. If the DPP candidate in 2016 can repeat the performance of the party's candidates in 2014, then 5.83 million votes is a conservative estimate of its vote total in these places in the next presidential election.

But what about the oddball places? Let's imagine that the DPP had run candidates in all these jurisdictions, and then assume that they performed as well on average as DPP candidates did elsewhere. In other words, assume that the increase in votes for the DPP in the oddball places would be proportional to the increase in the other, non-oddball places. That is:

DPP's net vote increase in normal jurisdictions, 2012 to 2014: 508,290

Total votes in normal jurisdictions, 2012: 11,246,356

Fraction increase: 0.045

Net increase in oddball jurisdictions, 2012 to 2014: X

Total votes in oddball jurisdictions, 2012: 2,107,949.

X is then 0.045*2,107,949, or 95,271 votes.

The Tsai campaign in 2012 won 771,762 votes in the oddball cases, so adding these up we get an estimate for 2014 of:

771,762 + 95,271 = 867,033.

Thus,

Non-oddball 2014 vote total: 5,830,106

Oddball 2014 vote estimate: 867,033

Estimated 2014 DPP vote total if candidates ran everywhere: 6,697,139.

So, in a hypothetical scenario in which the DPP ran candidates everywhere, the party's vote total for 2014 would be 6,697,139. That is just under 200,000 votes short of what Ma Ying-jeou won but about 600,000 more than what Tsai won in 2012. It's also higher than any DPP presidential candidate has ever won in the past--Chen Shui-bian's vote total of 6,446,900 in 2004 is the previous high-water mark for the party. For a "local" election with a turnout rate well below the last presidential election, that number is eye-opening. It's a clear indication that the DPP didn't win just because pan-Blue voters stayed home while pan-Green voters all showed up; instead, if you accept the calculations above, the DPP in effect captured more votes than it has ever won before, in any election, presidential, legislative, or local.

Generic Conditions Favor a DPP Win in 2016

Given that, the DPP should probably be viewed as a slight favorite to win the presidency in 2016 even under generic conditions--two high-profile, appealing candidates, a neutral economic environment, moderate ideological position-taking, and the absence of serious third-party challengers. Those are big "ifs": a lot can change over the next year. But it seems more likely that they will change for the worse rather than for the better for the KMT.

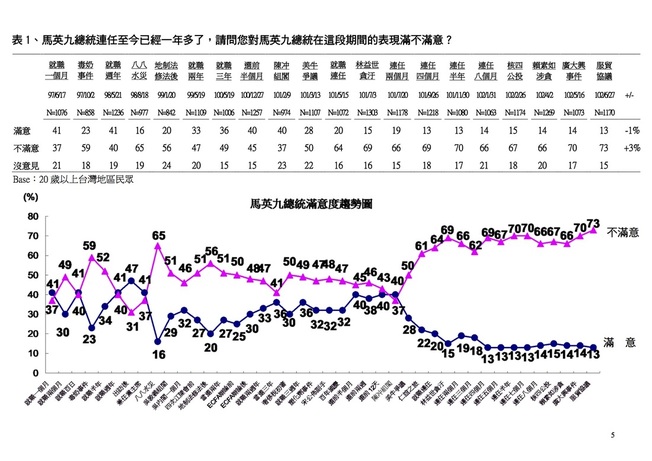

For one, while the DPP seems set to nominate Tsai Ying-wen again, the KMT does not have any obvious presidential contender waiting in the wings beyond Eric Chu. If he decides not to run, whoever the KMT nominee is will start at a serious disadvantage in name recognition and personal appeal. And if Chu does decide to run, he will probably need to put considerable distance between himself and the incumbent president in order to have a serious shot at winning. President Ma's approval ratings, and those of the Executive Yuan, have been consistently under 20 percent for most of his second term, giving the DPP the opportunity to frame the election as an anti-Ma vote as much as a pro-DPP one.

So, bottom line: unless there are major surprises over the next year, the 2014 election results suggest that Taiwan's next president will likely be from the DPP. For a party that has itself been on the receiving end of several electoral drubbings over the last decade, it's a remarkable political recovery.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed