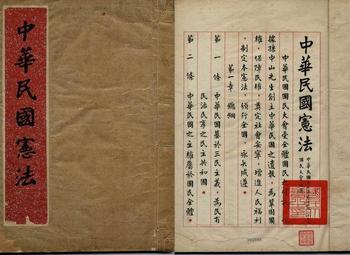

Republic of China constitution

Republic of China constitution At the heart of the current conflict in Taiwan over the Cross-Strait Services Trade Agreement (CSSTA) (兩岸服務貿易協議) is a legal dispute, possibly even a constitutional one. Despite its role in igniting the student occupation of the legislature, there's not much English-language coverage of the legal questions. (Student protestors and riot police make for better news copy--who knew?!) Nevertheless, most of the materials at issue are publicly available online, so I think it's useful to gather these in one place, along with my take*. If you need some background on the conflict, see my previous post.

The first thing to note is it's not clear from precedent whether agreements signed with the PRC under the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) (兩岸經濟合作架構協議) require legislative approval to take effect--because there is no precedent! The Ma administration has argued that the CSSTA is technically an Executive Order (行政命令), not a law or treaty. Furthermore, because it does not require the adoption of new legislation or amendments to existing legislation, the agreement does not require legislative ratification to take effect.

Second, the CSSTA (in Chinese here) is technically an "annex" to the ECFA (text here; special website is here). As with all agreements governing cross-Strait relations, ECFA and the subsequent CSSTA have to be negotiated and signed by the "non-governmental" bodies set up to avoid the question of Taiwan's legal status vis-a-vis the People's Republic of China. These are the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) (海峽交流基金會) on the Taiwan side and the Association for Relations across the Taiwan Strait (ARATS) (海峽兩岸關係協會) on the PRC side. The legal authority for negotiating cross-Strait agreements is delegated to SEF from Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Council (MAC), as specified in Article 4-2 of the Act Governing Relations between Peoples of the Taiwan Area and Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例). That Act is available in its entirety online, in English (here too) and in Chinese.

The key articles relevant to the current dispute are in Chapter I, Articles 4 and 5. Article 5 requires that agreements be submitted to the LY "for record" if no new laws or amendments to laws are needed. If new laws or amendments to existing laws are required by the agreement, then it must be submitted to the legislature "for consideration."

"For Record" vs. "For Consideration" (備查與審議)

That leaves the question of what submitting to the LY "for record" and "for consideration" means. From Article 5, the Chinese for "for record" is beicha (備查)--literally, “for future reference." The Chinese for "for consideration" is shenyi (審議). In practice, these terms indicate what the status quo is: if an executive order is submitted "for record", the legislature must review and either approve, reject or change the order within 90 days of its submission; if it does not, the order takes effect automatically. Thus, no action means the executive order stands. If an executive order requires new legislation, it also requires "consideration". If the legislature "considers" and takes no action, then the order does not take effect, and nothing changes. To use a more technical term, the reversion point in bargaining between the branches favors the executive under "for record" and the legislature under "for consideration" submissions.

The difference between these two procedures is the crux of the conflict over the CSSTA. The Ma administration's argument is that the cross-Strait Relations Act plus the ECFA is all the legal authority it needs to sign and implement the CSSTA. Any regulatory changes agreed to under the ECFA structure are administrative in nature, and can be implemented via executive order. And at face value, that's what Article 5 says: no new laws or amendments, no need for legislative approval.

The counter-argument (spelled out nicely here, in Chinese) is that ECFA itself is either a "prospective treaty" (準條約) or an "administrative agreement" (行政協定), but not a law passed by the legislature (立法院通過的法律), an act of authorization (授權法), or an organic law (組織法). So agreements reached by the SEF under ECFA authority cannot be treated like executive orders, because the SEF is not a formal administrative body. As a consequence, the CSSTA should be submitted to the legislature "for consideration" as a treaty, just like the ECFA was, and like the recently passed New Zealand and Singapore free trade agreements were.

A Legal Mess

Now, here's where things get messy. Neither side in this dispute has an airtight legal argument. After the agreement was signed in June 2013, the Ma administration wanted to submit the CSSTA to the legislature as an executive order, "for record." The opposition camp opposed that, of course, but Ma's position also raised concerns among KMT and PFP legislators. Speaker Wang Jin-pyng then negotiated an agreement among the party caucuses, including representatives of the KMT, to treat the agreement as "for consideration"--i.e. requiring legislative approval to take effect--and moreover, to review and vote separately on each item in the agreement. Once that decision was made, the agreement's review became subject to all the procedural rules in the LY that govern legislation. When Chang Ching-chung asserted that the 90 day deadline for review had passed, he was contradicting his own legislative caucus's position that the agreement would be treated like a treaty, not an executive order.

But on the other hand, if one reads the actual Act from which the SEF's negotiating authority is drawn, it explicitly says that no legislative approval is needed if an agreement can be enforced without new or amended laws. Here is Article 5, in English:

- Where the content of the agreement requires any amendment to laws or any new legislation, the administration authorities of the agreement shall submit the agreement through the Executive Yuan to the Legislative Yuan for consideration within 30 days after the execution of the agreement; where its content does not require any amendment to laws or any new legislation, the administration authorities of the agreement shall submit the agreement to the Executive Yuan for approval and to the Legislative Yuan for record, with a confidential procedure if necessary.

Given how controversial anything related to cross-Strait relations is in Taiwan, there is a strong normative argument for getting agreements ratified by the Legislative Yuan before they take effect. But the legal argument is much less clear-cut--just look at Article 5. And that ambiguity is a big problem for everyone, because it undercuts the legitimacy of cross-Strait policy-making, whether or not the CSSTA passes.

Shouldn't the Courts Resolve Legal Conflicts?

In an ideal world, the question of whether the CSSTA is an "executive order" would be resolved by the Council of Grand Justices, Taiwan's constitutional court. It's unfortunate the issue wasn't put before them, and I'm not really sure why--probably a combination of several reasons: the long time it takes to get a court decision, the Ma administration's haste to get the CSSTA through the legislature, the timing of the student occupation of the LY, and the court's own desire to stay out of partisan conflicts. At any rate, that option appears to be precluded now, and Taiwan's democracy is worse off for it.

Nevertheless, there may be a silver lining here. The Ma administration has belatedly appeared to acknowledge the legitimacy problem surrounding cross-Strait negotiations, and has proposed changes that would strengthen legislative oversight. The students occupying the legislature have proposed their own mechanisms for oversight. If some version of those gets adopted--including, crucially, a requirement that cross-Strait agreements be ratified by the legislature to take effect--then at least some of Taiwan's democratic institutions might actually come out of this crisis with a bit more legitimacy in the long run. And that's something people of all political stripes in Taiwan ought to approve of.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed