I’m skeptical that we are about to see this kind of realigning election, despite the attention given to the campaigns of the so-called “Third Force” parties. I’m also skeptical that this result will be the death knell for the KMT as a political party capable of winning elections. The KMT's coming defeat clearly reflects deep unhappiness with Ma Ying-jeou and the KMT’s rule over the last eight years, intensified by a spectacularly ill-timed economic downturn over the last few months (at least if you are a KMT member!) But an unpopular leader, toxic party brand, and disillusioned supporters are not fatal to major party survival, as the DPP showed after its 2008 electoral thrashing. So while a KMT recovery is not assured, and will at a minimum require some major leadership shakeups, we shouldn't expect the party simply to fade away, and for all those pan-blue supporters (still at least 30 percent of the electorate) to suddenly become fans of the DPP or one of the new parties.

Of course, I could be totally wrong--I'm just some guy on the internet, after all. But either way, we'll know a lot more soon: elections have a nice way of splashing everybody with a cold dose of reality. The results of the election this Saturday will give us the most concrete evidence we'll have to evaluate these competing narratives. So, in the interest of intellectual honesty, let me lay out my own expectations about what will happen, and what it means. Beyond who wins and loses, here's what I'll be watching most closely to see where Taiwanese politics is headed.

My expectation: the swing toward Tsai is still pretty uniform, ranging from a couple points less than the average in Taipei to a few points more in Taichung--evidence that voting behavior is being driven by the same factors as in the past. If we instead see wild (i.e. 20+ point) swings toward Tsai in some places, and small (<2%) or negative swings in others, that would suggest more fundamental changes in the electorate, and greatly strengthen the case that this is a critical realignment of the party system.

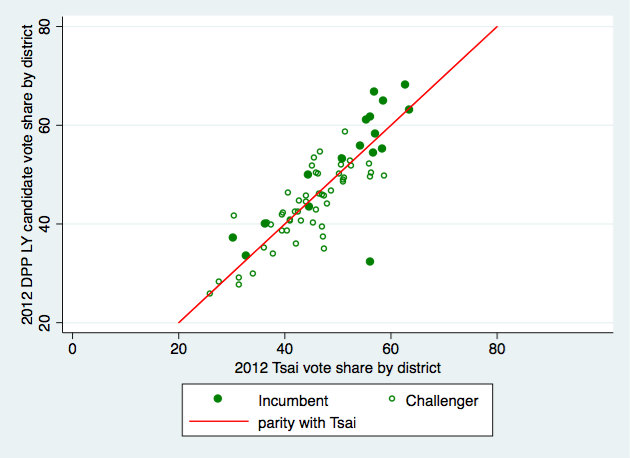

Two: How Close are DPP Candidates Running to Tsai? This has every indication of being a “wave” election: the KMT brand is so toxic in much of Taiwan right now that many of the party’s candidates have dropped the party’s logo entirely from their campaign posters. The great hope of KMT incumbent legislators is that they can survive the onslaught by personalizing the race, emphasizing their individual virtues and constituency service, and persuading many voters to split their votes between Tsai and a KMT representative. The closer DPP challengers are running to Tsai, the less split-ticket voting is probably happening among Tsai supporters, and the more likely the DPP is to win an outright majority in the Legislative Yuan.

A related indicator: how well do the non-DPP candidates endorsed by the DPP do relative to Tsai? Will DPP partisans actually come out and support NPP candidates like Huang Kuo-chang at the same rate that they vote for Tsai? The answer to that will tell us a lot about the NPP's electoral appeal and ultimate staying power.

My expectation: DPP challengers run 2-4 points behind Tsai on average, which is not enough to save most vulnerable KMT incumbents, and the DPP wins at least 45 district seats. The DPP-endorsed NPP candidates run another 2-4 points further behind Tsai; Hung Tzu-yung wins her race, but Huang Kuo-chang and Freddy Lim lose theirs.

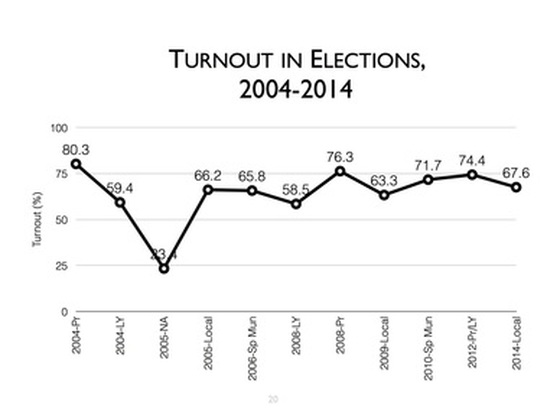

However, turnout was actually even lower in 2012, at 74.4%, despite the closer race and the combined presidential-legislative elections. So either of two scenarios seems plausible in 2012: turnout continues to decline from its 2004 high as more of the eligible population becomes detached from or disillusioned with politics (mirroring trends across the developed democracies), or anger with the KMT, Ma Ying-jeou, the poor economy, and the myriad other issues that have cropped up in the last four years motivate irregular voters to turn out this election, and turnout is closer to 2008 than 2012. The higher the turnout, the stronger the case that this represents a lasting shift in the electorate from a pan-blue to a pan-green majority, rather than an aberration brought on by a poor economy and pan-blues staying home.

My expectation: Turnout is above 2012, close to the level of 2008. As an interesting aside, it's worth noting that turnout in 2012 in some of the areas of the DPP heartland of Yunlin (68.9%), Pingtung County (72.7%), Chiayi County (72.5%) and Chiayi City (73.5%) was several points below turnout in the pan-blue stronghold of Taipei (76.8%). Without additional data, we can't know what caused this difference, or even that those who stayed home in the south were greener than the average voter. But it seems plausible that Tsai has slightly more room to increase her vote totals in these areas than she does in the north. I'll be very interested to see whether turnout here remains below the national average or not on Saturday.

Four: What Share of the Party List Vote Do New Parties Win? Much has been made of the rise of a “Third Force” in Taiwanese politics over the last two years—parties and activist supporters who are attempting to move “beyond green and blue” to take stands on issues that cross-cut the current party system orientation around cross-Strait relations. These include such disparate causes as environmental protection, social welfare policies, greater regulation of large corporations, women’s rights, opposition to nuclear power, support for or opposition to same-sex marriage, and inequality. By contrast, the current party system does not reflect this diversity of concerns. All four of the parties in the current legislature--the TSU, DPP, PFP, and KMT--can be differentiated by their stances on a single issue dimension: how to handle relations with the People's Republic of China. That issue has been the primary cleavage in Taiwanese politics for the last 25 years, despite many, many attempts by new parties to try to raise the electoral salience of other issues. (For instance, look at this list of parties to register over the years!)

The problem for today's new parties is that Taiwan’s single-member plurality-winner electoral districts do not give them much of a chance to win, leaving the 34 party list seats as the main target for most of these groups. And there are a lot of them this time around: the party ballot lists a whopping 18 different parties to choose from, including many that are brand new and running on platforms that do not obviously fit into the traditional blue-green divide. But the new parties face a serious signaling problem: most voters have no idea which parties will be viable and what they actually stand for, since they have no track record. So there could well be a lot of wasted votes here, with several parties winning between 1-5% of the vote. Whether or not any new parties make it into the legislature, the total share of this combined vote for new parties should be a decent indicator of latent concern in the electorate for issues beyond cross-Strait relations.

My expectation: new parties combined win at least 15% of the party list vote, but the only new party to cross the 5% threshold and enter the legislature is the New Power Party, which replaces the Taiwan Solidary Union at the green end of the political spectrum. And with the DPP, KMT, and PFP all still winning seats in the legislature, talk of a fundamental realignment of the party system around other issues besides cross-Strait relations will look premature.

Five: How Large is the Pan-Blue Vote? The last year has been a perfect storm for the KMT: it got trounced in the local elections in 2014, inexplicably failed to nominate a top-flight candidate in spring of 2015, and then after a prolonged period of infighting and uncertainty gave Hung Hsiu-chu the nomination. She quickly became a liability for the party, which created an opening for James Soong to declare yet another independent candidacy and compete for the support of pan-blues and blue-leaning independents. That, of course, set up an ugly 11th hour switch of the party's nominee, with Eric Chu replacing Hung, further angering key parts of the KMT base. And then on top of all that, economic growth turned negative in 2015.

All this is a long way of saying our default assumption should be that the 2016 election will be a low-water mark for the KMT. Everything that could go wrong, has. As a result, a lot of pan-blue supporters are going to abandon it this election (emphasis on this election): in the presidential race, Soong is going to get a lot of protest votes if the polls are at all accurate, and the PFP, MKT, and NP will probably peel away a significant chunk of its LY support and throw some seats to the DPP. The KMT is facing renegade pan-blue candidates in many districts it should win easily, and it may well suffer embarrassing defeats in some of them (such as Hau Lung-bin in Keelung). But it's misleading to conflate the KMT's fate in this election with a collapse in pan-blue partisanship, which remains significant.

The latent electoral support for the combined pan-blue camp is both the hardest to measure and the most important for the future direction of Taiwan's party system. But two indicators should give us at least a rough idea of this level: the combined pan-blue (Chu + Soong) vote in the presidential race, and the combined pan-blue vote (KMT+PFP+pan-blue renegades) in the district races.

My expectation: both the combined pan-blue presidential and LY district vote shares will be well above 40%. (For reference, in 2008, the DPP's presidential candidate got less than 42% of the popular vote, and the party's district candidates carried only 38%.) If the pan-blue vote falls much below those benchmarks, then the case that this election represents the start of permanent KMT decline becomes considerably stronger.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed