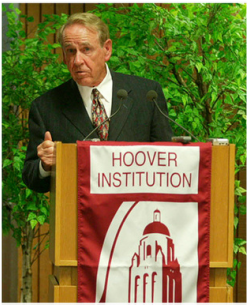

Myers was the former curator of the East Asian Collection at the Hoover Institution, where he played a central role in acquiring new materials on Taiwan's post-war history, including a vast collection of documents from the KMT party archive in Taipei as well as the Chiang Kai-shek diaries.

He also wrote several influential books and articles on Taiwan. The best-known in Taiwan studies is probably The First Chinese Democracy: Political Life in the Republic of China on Taiwan (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, 2nd ed. 2002), with Linda Chao, but he also co-authored a history of the 2-28 Incident in 1947 and co-edited a widely-read volume on the Japanese pre-war colonial empire, among others.

For those interested in a personal history of sorts, I recommend this interview conducted by Hsiao-ting Lin and Da-chi Liao in 2007, before he retired as curator. It gives a fascinating view into the practical challenges and opportunities and the intellectual cross-currents faced by his generation of East Asia scholars. I've excerpted a particularly interesting bit below:

Why did Hoover want to recruit you?

Good question! The curator was a Chinese gentleman called Ma (馬). His predecessor Eugene Wu had been in charge of the Yenching Library at Harvard. Before him was Mary Wright. I also took the name Ma (馬). The first Ma was only at Hoover for 6 years, but he had a very serious problem with women. Several of them went to Director Glenn Campbell and complained. Campbell offered Ma the choice of resigning or being fired. Campbell wanted a curator who was also a scholar and a fundraiser. I did not know about all these internal developments until I had been here 2 years. I applied to be a senior fellow, and the committee concurred. Finally, the President of Stanford University agreed.

Did you have connections with Taiwan then?

No. That came 2 years later. Wei Yong (魏鏞) had been a National Fellow at Hoover in 1974. But he left to take up a job in Chiang Ching-kuo’s cabinet. Campbell and Wei Yong and also Yuan Li Wu (吳元黎) helped me to visit Taiwan. Richard Starr, who was Campbell’s deputy, suggested I take a couple of trips to Taiwan. Based on these travels, I developed a friendship with many in the KMT.

With Lee Teng-hui (李登輝)?

I met him much earlier, when I went to Taiwan in 1959. He was at the Nong Fu Hui (農復會) and Taida’s Agricultural Economics Department (台大農經系). We were once at conferences together, and admired one another’s agricultural economic work, which was the focus of our dialogue. When I went back on short 2-3 week trips to meet Taiwanese people, I developed an interest in the KMT, and began to learn about Taiwan; one thing led to another. I wrote a book on the February 28 Incident (二二八事件) with two other Chinese scholars. Next visit was to go to the Sun Yat-sen University in Kaohsiung (中山大學) in 1982-83.

How did you know Qin Xiaoyi (秦孝儀)?

That was also accidental. When Qin made his first visit to the US in 1984, he was invited to the Association for Asian Studies annual meeting in Chicago. He wanted to come to Hoover or Stanford to get some publicity. I learned of his desire to visit Hoover before going to Chicago. So I arranged for Qin to come here. He gave a talk in the reading room of the East Asian Library. We had a huge audience for him to address. He got a lot of publicity in the local newspaper about being invited to speak here. He was very grateful and so he and Lee Huan (李煥) arranged for Edna (my wife) and me to go to the Sun Yat-sen University (中山大學). Qin used his connection with Hoover to gain support from among the Chinese community. This worked out very well for him and for us. Then when I went out to Sun Yat-sen University, my ties with the KMT became closer. I would say the Qin Xiaoyi’s trip in 1984 was very important.

Didn’t you know him before that?

I only had met him when he came to Hoover, and also two years later when Edna and I visited Kaohsiung. I also met Kuo Ta-chun (郭岱君), who came here on a grant from Institute of International Relations, National Cheng-chi University (政大國關中心). She came to Hoover and worked with me on a long article, which became a book on how to interpret Communist China. We published it at the Hoover Press, and many people used it. In the early 1980s, Western scholars were trying to re-evaluate the achievements of Chinese Communism, particularly Mao Zedong. Our book was a comparison of how good the work of Taiwanese China-watchers compared with that of Europeans and America’s. I think we omitted the Japanese. We pointed out, quite credibly but controversially, that the Taiwanese Chinese-watchers were the best: they had met and were with Communist revolutionaries when they were doing underground spying. They had inside documents from intelligence sources far much better than we had. They could make powerful arguments about CCP rule of China and interpret change. Where they did best was interpreting how China was having a series of problems with the Communist system which proved that its problems were serious.

...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed