A little background first: since 1995, Taiwan has had a mixed-member electoral system (混合制) with two parallel electoral tiers. Up until 2004, the larger, district-level tier consisted of between 25-30 multi-member districts (複數區), with multiple representatives elected from each district using the single non-transferable vote (SNTV) (不可轉移單票制). The smaller, national-level tier consisted of a single nation-wide district in which seats were awarded to parties using closed-list proportional representation (CL-PR), based on the percentage of the vote that each party's district candidates won aggregated across all districts. A major reform* before the 2008 election halved the size of the legislature, replaced the multi-member districts with single-member ones, and introduced a separate vote for the PR tier, but retained the closed-list rule for the PR seats.

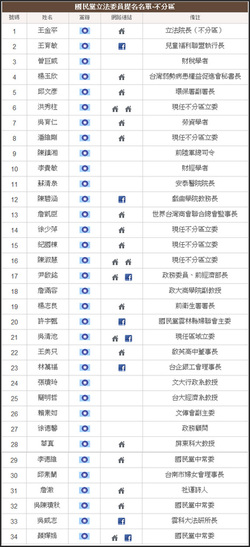

The "closed" part of "closed list" PR means that the party, not voters, controls who gets these seats. It does so by submitting a ranked list of names (分配當選名單) prior to the election; when the seat totals for each party are announced, the PR seats are distributed down the list until the party's quota is met. For instance, in the 2012 legislative election, the KMT won 16 seats in the PR tier, so the top 16 candidates on its party list were awarded seats. This is how Wang Jin-pyng was most recently elected: he was ranked first on the list. (You can find the lists for this and other elections at the Central Election Commission website. The image at right was pulled from here.)

It is not hard to see that the order of names on the party list goes a long way toward determining who gets seats. The first candidate on the list is as good-as-elected once the list is submitted, unless the party fails to win any PR seats. But the 16th candidate will have to sweat out the election. And the 34th candidate has no realistic hope of winning a seat whatsoever. Thus, whoever controls the party list controls the electoral fates of all the PR legislators. Typically, party leaders determine the ranking and put themselves and their allies** at the top of the list, while incumbents who've ticked off the party leadership get left off entirely. So legislators elected from the PR tier have to toe the party line if they want to remain in office.

But that's not all. Taiwan electoral law also provides political parties another weapon to keep list legislators in line: the Civil Servants Election and Recall Act (公職人員選舉罷免法) specifies that any at-large legislator who loses his party membership will also immediately lose his seat. Hence why Wang Jin-pyng was so vulnerable to a purge by President Ma: as an at-large legislator, his seat depends on the continued tacit support of the rest of the party. Rather than wait until the run-up to the next election to deny Wang his previous position on the party list, Ma and his allies could remove him immediately by stripping him of his party membership. It is only through a rather surprising, and lucky, district court injunction that Wang has so far survived the attempt to boot him from the legislature.

It's noteworthy that Wang Jin-pyng has not always been an at-large legislator for the KMT. Until 2004, he was one of several legislators representing Kaohsiung County's First District, and a quite popular one at that. If he were still a district legislator, stripping him of his party membership would not have had the same effect; he would have retained his seat. That raises the question, why would a leading politician like Wang ever join the party list?

The answer is that it’s a sure-fire way to get into the legislature without having to win a district-level election. Campaigns for legislative district seats were notoriously fierce, and costly, under the old SNTV system, because candidates had to compete for votes not only against nominees from other parties but also with their own fellow party members. Winning a seat usually required relentless effort to differentiate oneself from everyone else and cultivate personal ties to constituents. (And, all-too-frequently, some form of vote-buying.) So when Wang first ran on the party list in 2004, when SNTV was still in place, it was undoubtedly appealing to him to leave behind the trouble of district campaigning. The switch to single-member districts in 2008 eliminated most intra-party competition, but at that point Wang was already ensconced at the top of the KMT list and had no reason to return to a district.

Now, of course, he does. My money is on him returning to his old Kaohsiung County district and running there in 2016, where he retains a base and can probably win comfortably. Whether or not he hangs on to his seat through the end of this term, I doubt we have seen the last of Speaker Wang.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[* Taiwan's history of electoral system changes is dauntingly complex, even post-martial law era. I will attempt to cover it in a future post.]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed